Where There’s a Wool, There’s a Way: Eight Faroe Islands Startup Teams to Watch in 2021

Table of contents

Sheep may still far outnumber the 50,000 people who live on the islands, but the Faroes have a close-knit and entrepreneurial community. The Org spoke with eight startups that embody the islands’ daring, diverse and dynamic approach to doing business.

Globe Tracker

90% of all goods in global trade spend time in a container; 30% of perishable goods are spoiled on their way from farm to fork. This spoilage tends to happen as goods travel across the seas in reefer containers, and is often due to issues with humidity or temperature. Globe Tracker was established to minimize this using telematics.

“We basically put a hardware device in the reefer container, which enables you to have visibility of where the container is, and to change settings in the container,” Globe Tracker VP of Sales, EMEA, Richard Jacobsen explains. “So you can change humidity, temperature, and you can also be notified if the temperature deviates from the expected temperature and so on.”

After years of quiet product development, Globe Tracker is now experiencing a hockey stick-shaped growth trajectory, with customers including Hapag-Lloyd, Dole and Seaboard Marine. “I believe we started out before there was a demand in the market. But now the demand is huge,” Jacobsen says. “We're experiencing growth rates of 150% a year, and we have a number of very large shipping lines that use our solution.”

Indeed, the global pandemic, and even the Suez canal blockage, has only increased the demand for Globe Tracker’s solutions.

Expecting to double its headcount by next year, Globe Tracker’s current 50-person team is spread across hubs of expertise around the world. It has core IT and software engineering teams in its Torshavn headquarters and in Iceland; engineering and hardware expertise in the US; and trade-line offices in Singapore and the Netherlands.

Backed by Faroese investments, including fishing company Framherji and a local life insurance company, Globe Tracker has raised $22M to date. With fish making up 95% of all exports from the Faroe Islands — all transported out in reefer containers — it was easy for Faroese fishing companies to see the potential in Globe Tracker’s solution. “Be it fish, meat, vegetables, medicine, blood plasma, everything which is perishable goes in a reefer container,” Jacobsen says. “So we created a local solution, which was fitted to a global supply.”

Thetis

Established in 2016 by Marita Magnussen and Regin Dalsgaard as the first private laboratory on the Faroe Islands, Thetis was originally started for food and environmental tests, working closely with the fishing industry and local councils.

But then the coronavirus hit.

“We already had the equipment and the experiment experience,” CEO Magnussen says of the company’s decision to do COVID-19 samples.

“So now we are doing environmental samples and food samples, and corona samples via PCR tests and antibody tests.”

When the Faroese government was looking for a way to keep the borders open last year, Thetis got tasked with providing the border testing. “We have people in the borders, working around the clock every day of the week,” Magnussen told The Org.

Then last year in August, the island experienced a large outbreak. “There were several thousand people waiting for results, and then the inland testing was also given to us because we have a big capacity.”

As Thetis’ work expanded to the majority of both the inland and border testing, it saw its team scale from six to eighty people in just three days. Naturally, the team’s modus operandi is total flexibility, at all times.

“Everything is possible. If you call three o'clock in the night and you want your crew tested on the ship, it is no problem. We will fix it,” Thetis Chairman Regin Dalsgaard says. Magnussen adds “since corona, that's always been our trade-mark. We always work seven days a week, 24 hours. You can always get a hold of us.”

Combining Magnussen’s experience and PhD in medical science, and Dalsgaard’s entrepreneurial background (including his co-founding of a fellow startup on this list - Nemlia), the co-founders believe in a flat organizational structure, where all employees are involved -- and that approach has proven a winning formula for securing the islands’ safety.

Ocean Rainforest

In the wake of a decades-long Faroese fish farming boom, ‘algae-preneur’ Ólavur Gregersen is leveraging local oceanic engineering expertise to enable offshore seaweed cultivation, developing systems that are scalable and don’t get swept away by storms.

His 12-person team operates out of a refurbished fish processor that now serves as a seaweed hatchery and refinery. If Ocean Rainforest can scale enough while keeping a low price point, Gregersen believes that seaweed will have high value potential as a healthy additive in food and feed, with an ability to reduce methane emissions in ruminant animals.

It could also replace fossil-based products such as plastic and fuels while serving as a useful way to sequester carbon.

“The Faroes is the perfect testbed for any technology you want to do in the ocean,” Gregersen, who earlier this year netted $1.5M in funding from the World Wildlife Fund, says. Currently the company is working towards another harvest at its offshore rigs in the summer and anticipating the arrival of a special purpose harvesting catamaran.

Meanwhile in the U.S., the firm is leading a consortium demonstrating the feasibility of a similar system off the coast of California in the Pacific Ocean, with significant funding from the U.S. Department of Energy’s ARPA-E Mariner program. Gregersen believes the governments of California and the Faroe Islands both need to be more streamlined in the way they oversee the budding industry.

With a 60-40 female to male ratio on his multidisciplinary, multinational and multigenerational team, Gregersen points out that team members often have to be just as prepared to apply academic brain power as they are to get stuck into menial work at the processor, or to don a hard hat and take to the ocean with the skipper at harvest time — brandishing machetes.

“As we’re building something from scratch, we have to be very innovative all the time,” he says. “We can't afford to have an overhead staff of academics and then other people to do the manual work. We all have to do what's necessary.”

Faer Isles Distillery

Faer Isles Distillery is on a mission to make gin and whisky on the windswept, salty shores of the Faroes — much like the Scots and the Irish use their shores to the south, with the exception that distilleries were banned in the Faroes right up until 2017.

The end of that ban spurred Bogi Mouritsen to act quickly; he quit his job of 25 years as an IT consultant, sold his apartment in Copenhagen, and moved to the Faroe Islands. His co-founder D√°nial Hoydal followed suit a year later.

The pair had already founded the first-ever Faroese whisky appreciation society EinMalt 13 years ago. When launching Faer Isles’ founders club last year, 1100 fellow whisky enthusiasts from 22 different nations signed up as founding members. Adding to the community-driven funding model, from March until August this year anyone can buy a share of the company – even with cryptocurrency. Faer Isles is the world’s first distillery to enable crowdfunding through a security token offering.

Currently, the distillery’s first test batches are underway, and the company’s four-person team already has building plans in place for a full-scale whisky distillery, along with a visitors centre overlooking the fjord, located next to the old viking village of Kvívík.

The plan is all part of bringing whisky distilling and maturation to where the team believes it belongs: The untouched Faroes with its abundance of clean surface water, a humid climate with green grassy hills, and high winds that whip up salt from the sea.

In the maturation process, Faer Isles will use traditional Faroese opnahjallur: small, grass-roofed cottages normally used for drying meat or fish. With their narrow wooden slats the opnahjallur provide barrels with full exposure to the salty winds for fermentation and preservation. Embracing the Faroese climate and nature, gin botanicals are similarly sourced from the surroundings — including juniper, angelica, nettles and the team’s signatory ingredient: seaweed (which is procured from another team on our list, Tari).

Tari

Seaweed is a hot trend in the Faroe Islands, with models catwalking in algae-infused outfits aboard wave-tossed fishing boats.

But far before high seas couture, there was Agnes Mols Mortensen, the lone Faroese seaweed microbiologist.

While she now revels in how the tide has turned, she worries about the ecological downsides of too much fresh commercial attention without the science to back it up. With that in mind, she founded Tari with her brother and a note of caution: “We need to make sure that anything we start doing in ocean production is not damaging ecosystems in any way.”

Mortensen distances herself from other seaweed producers, saying some are charging in without enough surrounding research. Instead, she finds herself in a small array of local partnerships on the island, producing “ocean spaghetti,” and even providing oceanic aromatic essences for the Faer Isles Distillery.

Another significant revenue stream for Tari comes from the fish farming industry via lumpfish shelters. There, fish are bred to swim among salmon and nibble away parasites like lice. Mortensen provides shelters made of seaweed to help the lumpfish maintain their own health and wellbeing.

So far, she has expressed a reluctance to accept outside funding except research grants like those from the EU funded SW-Grow project, expressing concerns that investors could prioritise scale above sustainability.

Sea Farm Innovations

The recent documentary Seaspiracy shines a harsh light on the global fishing industry, with its film crew flying to the Faroe Islands to shoot gory footage of local whale hunting. But they might have got a fuller view of what the Faroes are bringing to the fishing industry by talking to a team like Sea Farm Innovations, which is developing a suite of technologies to massively boost fish health and welfare.

Starting off as some father-and-son garage bonding time, Faroese engineer Eyðbjørn Hansen got to work building what would become “a patented flushing method.” Knowing the fishing industry’s major problems with lice infestations, Hansen saw a key use case for it as a next generation hydrolicer. Conventional methods, on a large scale, can be chemically intensive, hazardous, or even fatal. His team’s aim: to bring cleaning methods down to zero fatalities with a kinder, faster and gentler process.

Sourcing further expertise from his family, he teamed up with his brother Ari, a marine architect, and Gunnar Johildarson. Already, the founding trio has had commercial success in a major set of sea lice removal deals with fish farming giant Cermaq. The deals bring the Sea Farm Innovation hydrolicers to aquaculture operations as far flung as Chile and Canada. Further growth should come through a wholesale agreement with big pump producer Grundfos.

“If you do not limit your thoughts then anything is possible,” CEO Eyðbjørn Hansen says. “It is a very good country to develop and test new things, the companies are small and there is a short way to top decisions , and that makes it faster and easier.”

Staying true to the Faroese spirit of going it alone, Sea Farm Innovations has largely bootstrapped its way to growth, so far only receiving a small grant from the Faroese government’s investment arm Vinnuframi. Though now, Hansen says they are looking for more capital to scale.

Nemlia

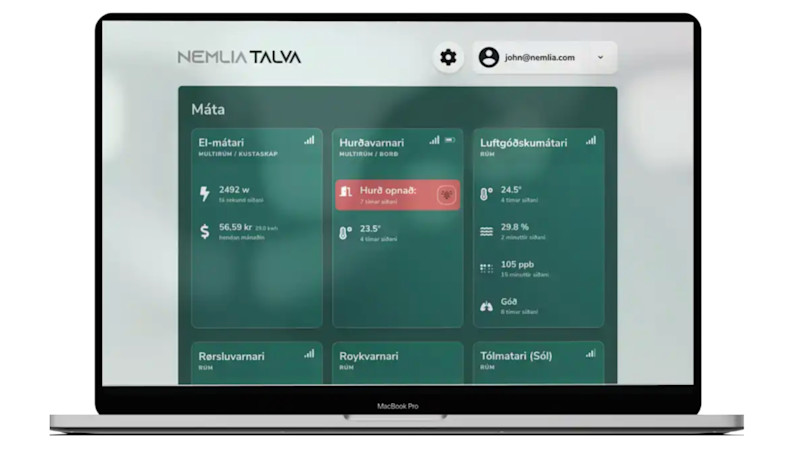

Nemlia wants to give elderly a better quality of life, while providing a better work environment for caregivers and reassurance for loved ones.

The medtech startup brings IT solutions for care homes and private homes, integrating sensors for smoke, heat or movement, that notify relatives and care workers if something is out of order.

“You need a system that allows you to be given notification when something happens that shouldn't happen, or something that should happen doesn't happen,” Peer Bentzen, CEO of Nemlia, explains.

Hailing from a family of healthcare and care providers, Bentzen joined Nemlia as CEO earlier this year. He comes with 25 years of experience in working with digitalization for companies like AOL, Microsoft and DHL, and wants to apply his skills to develop human-centred solutions. “The job of technology is to support the humans in doing what humans do best, and make what they do even better,” Bentzen says. “It’s not about technology, it's really about giving other people a better quality of life.”

The team of six includes former nurses, caregivers, anthropologists and technologists. Since launching its services, Nemlia has established close collaborations with local care homes and is currently operating in eight (out of the existing thirty) on the Faroe Islands. The startup is also in the process of expanding their B2B SaaS offerings to private homes.

“The decision roads on the Faroe Islands are much shorter, and that is hugely valuable,” Bentzen says, adding what he’s achieved in two months on the islands would have taken much longer in the German market. However, he adds there is an inevitable drawback: “You cannot scale on the Faroe Islands.”

To address that, the startup is looking abroad and is gearing up for entry into the French, English and German markets. The hope is that its solutions can help the rapidly growing demand for eldertech across the world, as the number of over-65s continues to outpace the growth of younger generations.

FarPay

FarPay got its start in 2014 offering integrated payment solutions and automated accounting software. The tiny size of FarPay’s initial target market — intuitively a red flag — in fact proved a positive, combined with how the four founders knew all the key potential customers.

“It’s an amazing sandbox to play with,” CEO Samal Samuelsen says. Samuelsen joined the team in 2016 at the beckoning of FarPay’s founders — his former colleagues at a financial firm in Copenhagen. “We knew all the key potential customers.”

Colleague and CTO Bárður Háskor noted how smaller companies also made for greater agility for dealmaking in the Faroes. He recalls his first prospective customer telling him he would “have to think about it,” before walking out the door, smoking a cigarette, and coming back in ready to sign.

With the product now stress tested, the team has been eager to roll out its accounting and omnichannel payment services across Denmark, Greenland and other Nordic countries — and the company plans on hiring a range of developers and marketing and sales employees.

FarPay has bootstrapped it as far as possible, taking funding from Denmark’s Vaeksfonden and the Faroese public VC Framtrak, while keeping equity in founder hands and turning to early revenues as a fuel for further growth.

Háskor says that in marketing, the company has actually recently become “much more of a Faroese company,” and it seems to be a place that a lot of business partners seem especially keen to drop in for meetings.

Looking back on his career path, Samuelsen jokes he had childhood dreams of becoming a fisherman, but then “got seasick” and emigrated to Copenhagen. That was the Faroes of the 1990s, with limited educational opportunities in a coastal community still hell bent on banning alcohol (the founder of wine app Vivino emigrated at a similar time.) Brain drain back then was rife.

But these days, Samuelsen sees his birthplace with new eyes. He finds himself working remotely from Copenhagen at a fintech headquartered back in the Faroe Islands. “I can definitely see a big change ... the brains for developing our product are all in the Faroe Islands."

--

The Org is a professional community where transparent companies can show off their team to the world. Join your company here to add yourself to the org chart!

In this article

The ¬Ð¿Ú¬“¬◊ helps

you hire great

candidates

Free to use – try today