- Iterate

- Meet The Team

- 'Like Turkeys Voting for Christmas:' The Vested Interests Delaying NZŌĆÖs Open Banking

'Like Turkeys Voting for Christmas:' The Vested Interests Delaying NZŌĆÖs Open Banking

Open banking puts the power back in consumers' hands by giving them control over their own financial data. It's becoming the norm in economies all over the world and has led to booming new fintech apps. New Zealand used to be a global leader in adopting new financial technology, but why are they falling behind in open banking?

Late last year, as most of the world twiddled their thumbs indoors, New Zealanders were in a state of frenzy. After a few months of locking down, the economy was back in action and the housing market with it.

Prospective first home buyers stood at auctions where sold for nearly $1 million over their values and lines for open homes stretched around neighbourhood blocks. As these buyers battled to get their foot in the front door, the banks were holding things back. High demand meant that getting a mortgage approval was taking at a time when any extra day waiting could cost tens of thousands.

In and the a solution to these delays is on the near horizon. Using simple apps, consumers will eventually be able to share their customer data with a third party fintech to quickly determine whether they are granted a loan or not.

ItŌĆÖs part of a wider global shift known as open banking.

In short, open banking is about customers ŌĆö not the banks ŌĆö having control over their own data. To do this, banks must build a common application programming interface (API), meaning that all information is being shared in the same language. The shared APIs allows all kinds of specialised fintechs to provide services that banks have traditionally had a monopoly on.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs actually the customerŌĆÖs data, not the bankŌĆÖs data,ŌĆØ said Travis Tyler, Chief Product and Marketing Officer at 86 400, which in 2019 became AustraliaŌĆÖs first neobank to receive a full banking license, in an interview with The Org. ŌĆ£So how can we help a customer better understand their data, to lead to better products and better experiences?ŌĆØ

As a digital bank, 86 400 is among the many Australian startup fintechs benefiting from their governmentŌĆÖs mandated transition to open banking. Australia shares company with Singapore and the UK in their accelerated uptake of open banking, something that has had incredible downstream impacts on both customer options and innovation among smaller fintechs.

In the UK last year, , while in Singapore, the addressable loan market for digital banks is valued at around .

In New Zealand, on the other hand, adoption has been comparatively snail paced.

If rhetoric was anything to go by, New Zealand would rank amongst world leaders in open banking. The reality on the ground isnŌĆÖt quite so rosey.

ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs been too much talk about it. As a nation, weŌĆÖve waited to see how it rolls out in other jurisdictions in the world,ŌĆØ said James Brown, CEO of industry group Fintech NZ.

In May of 2019, Payments NZ kicked off a project called the API Centre to create a common API standard for the industry to move forward on. Early signs from the collaboration between the big banks, government, and fintechs left so much to be desired that later that year, then Commerce Minister Kris FaŌĆÖafoi penned venting his frustration at an industry failing to move.

In it, FaŌĆÖafoi asked to see urgent progress of common standard APIs and ŌĆ£a range of products or services delivering value safely and securely for consumers.ŌĆØ

A year and a half down the track, and it would be hard to argue that the industry took this letter seriously. When approached by The Org to see how the government felt like things had progressed, they were typically tight lipped.

ŌĆ£We consider this work to be important and expect API providers to continue efforts to progress the implementation of open banking,ŌĆØ said a Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment spokesperson in a statement to The Org.

For some, the severe delays are a symptom of a majority foreign owned banking sector with too much leverage over regulators.

ŌĆ£You donŌĆÖt have a government with the ability or wherewithal to impose this as aggressively as they would like to,ŌĆØ said Sam Stubbs, CEO of retirement fund manager, Simplicity. ŌĆ£There is a tremendous fear amongst regulators where as soon as the banks rattle their sabres, everyone jumps up and pays attention.ŌĆØ

To try and get the ball rolling on the regulatory side, the governmentŌĆÖs business arm last year took on public submission for a Consumer Data Right (CDR), not dissimilar to the Australian CDR introduced three years before.

For Lewis Billinghurst, Head of Digital Ventures for Westpac New Zealand, the CDR is the ŌĆ£missing piece of the puzzle.ŌĆØ Westpac counts among New ZealandŌĆÖs top four banks, which collectively took home $4.14B in profits last year, COVID withstanding. He said in an interview that with proper legislation in place, heŌĆÖs confident that we will see open banking adopted in New Zealand ŌĆ£by the end of this calendar year."

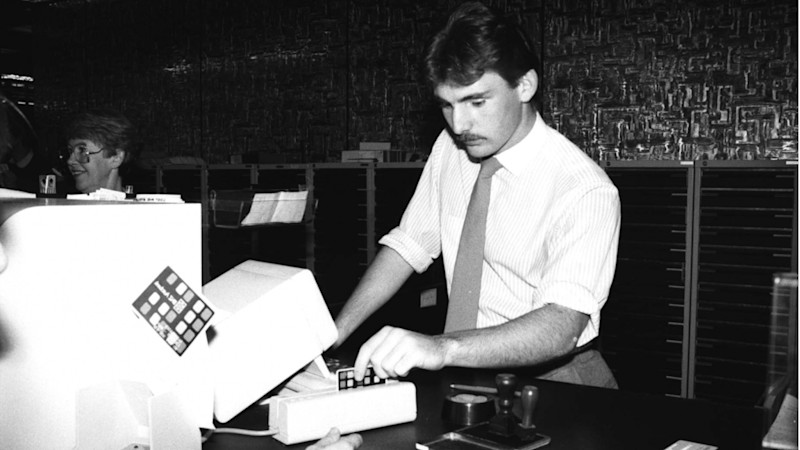

Somewhat ironically considering its sluggish uptake of open banking, New Zealand made a name for itself early on as a fintech innovator.

In the mid 1980s, New Zealand put the cash in the trash and became one of the worldŌĆÖs first, and by far keenest adopters of EFTPOS for transactions. While most countries around the world were still stuck using checks, most Kiwis were paying for their walkmans and shoulder padded jackets using credit and debit cards.

To achieve this groundbreaking feat, the banks had to work together closely.

ŌĆ£When itŌĆÖs in the banksŌĆÖ interests to make something happen, they can do it real quick,ŌĆØ said Simplicity's Stubbs.

When itŌĆÖs not in the banksŌĆÖ best interest, less so. Regulators in the UK and Australia were famously heavy handed in forcing open banking into their economies, New ZealandŌĆÖs regulators on the other hand have been far more permissive ŌĆö putting the impetus on the banks themselves to make the changes.

WestpacŌĆÖs Billnghurst was defiant that thereŌĆÖs been ŌĆ£no heel dragging at all,ŌĆØ but the evidence tells a different story.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs like turkeys voting for Christmas,ŌĆØ said 86 400ŌĆÖs Travis Tyler. ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs no incentive for incumbents sharing their data.ŌĆØ

And while there are still some proponents of the industry-led approach, like Fintech NZŌĆÖs James Brown (which lists several of banks in its membership), even the big banks have come around to recognising the conflict of interest.

ŌĆ£Everything is easier in retrospect,ŌĆØ said Billinghurst. ŌĆ£Originally it probably was the right direction, but you could argue that if we had started like Australia did with a regulatory push, we would have got the same outcome faster.ŌĆØ

In 2018, startup CoGo launched its app into the UK to help consumers see the social impact of their spending ŌĆö despite the entire team being based in New Zealand. While the company has slowly moved into its native market through screen scraping, the delayed New Zealand launch speaks to a more insidious issue about the innovation the country never saw.

For Stubbs at Simplicity, which has more than 50,000 customers and $2.7B NZD in funds managed, offering some aspects of banking services should be a real possibility.

ŌĆ£We have the resources to perform some banking services but thereŌĆÖs no way we would even think about it until there's common standard APIs,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£I think the loss in innovation for New Zealand [from delay] is in the billions.ŌĆØ

Delays notwithstanding, the arrival of open banking in New Zealand is almost certainly inevitable. This begs the question of how disruptive this will ultimately be to the banksŌĆÖ bottom line.

ŌĆ£You have a highly concentrated banking sector here, and a highly profitable banking sector here. So there is a huge incumbency effect. The idea of open banking is a complete inathema of that,ŌĆØ said Stubbs.

Whether the meteoric rise of open banking will help or hinder banks internationally is up for debate, but what is clear is that an open banking regime will eat at least some of the bankŌĆÖs lunch.

ŌĆ£I agree that it's a threat if we didnŌĆÖt move,ŌĆØ said Billinghurst. ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs a big threat in the medium term, where consumers want different ways of interacting with their money, and if their banks donŌĆÖt enable that, theyŌĆÖll switch banks. So itŌĆÖs a threat if you stand still.ŌĆØ

There are of how disruptive open banking will be to banksŌĆÖ profits, as specific services are replaced by smaller startups.

ŌĆ£Whether it be a niche proposition like wealth management or payments, or something broader like building a whole new mobile banking interface. For us, the upside [of open banking] is exciting for us, rather than any downside,ŌĆØ said Billinghurst.

One only has to look at the recent activity among the big banks to see how seriously theyŌĆÖre taking this. 86 400 is in talks for a planned acquisition by National Australian Bank, ASB has been investing in companies like and Airwallex, and Westpac in local fintechs like CoGo and Akahu.

NZ banks are hedging their bets for the inevitable tsunami of open banking over the next several years, but whether that will be enough is a guessing game.

ŌĆ£Up until now there has been no effective competition, but that's going to change,ŌĆØ said Stubbs. "The shift to open banking is going to completely flip things for the banks.ŌĆØ

Create your own free org chart today!

Show off your great team with a public org chart. Build a culture of recognition, get more exposure, attract new customers, and highlight existing talent to attract more great talent. Click here to get started for free today.

In this article

The ┬▄└“┬ę┬ū helps

you hire great

candidates

Free to use ŌĆō try today